A new technique that allows real-time, noninvasive imaging of the immune system’s response to the presence of tumours offers a potential breakthrough both in diagnostics and in monitoring efficacy of cancer therapies. Developed in the lab of Whitehead Institute Member Hidde Ploegh, the method utilises the imaging power of positron emission tomography (PET) to identify areas of immune cell activity associated with inflammation or tumour development.

“Every experimental immunologist wants to monitor an ongoing immune response, but what are the options?” Ploegh asks rhetorically. “One can look at blood, but blood is a vehicle of transport for immune cells and is not where immune responses occur. Surgical biopsies are invasive and non-random, so, for example, a fine-needle aspirate of a tumour could miss a significant feature of that condition.”

Knowing that the tissue around tumours often contains immune cells such as neutrophils and macrophages, Ploegh and his colleagues hypothesised that appropriately labelled VHHs — single-domain antibodies made by the immune systems of animals in the camelid family — might allow them to pinpoint tumour locations by finding the tumour-associated immune cells. (Ploegh’s lab immunises alpacas, his camelid of choice, to generate VHHs specific to immune cells of interest.)

Ploegh notes that VHHs’ extremely small size — about one-tenth that of conventional antibodies — are likely responsible for their superior tissue penetration and thus makes them particularly well suited for such use. For this study, the lab generated VHHs that recognise mouse immune cells, then labelled these VHHs with radioisotopes, and injected them into tumour-bearing mice. Subsequent PET imaging detected the location of immune cells around the tumour quickly and accurately.

“We were able to image tumours as small as one millimetre in size and within just a few days of their starting to grow,” explains the study's first author Mohammad Rashidian, a postdoctoral researcher in Ploegh’s lab. “We’re very excited about this because it’s a powerful approach to pick up inflammation in and around the tumour.” The study is published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The researchers believe that With further refinement the method could be used to monitor response to — and perhaps modify — cancer immunotherapy, which, though quite promising, has thus far met with great success in some cases, but has failed in others.

“To succeed with immunotherapy, we need more information about the tumour microenvironment,” Rashidian says. “With this method, you could perhaps start immunotherapy, and then, a few weeks later, image with VHHs to figure out progress and success of treatment.”

Adds Ploegh: “PET imaging should allow a much more comprehensive look at the entire tumour in its environment. Then we can ask, ‘Did the tumour grow? Did immune cells invade? What has happened to the tumour?’ And to be able to see this without going in invasively is a significant achievement.”

Source: Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research

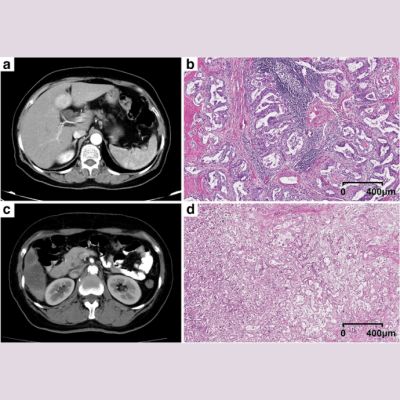

Image Credit: PNAS

“Every experimental immunologist wants to monitor an ongoing immune response, but what are the options?” Ploegh asks rhetorically. “One can look at blood, but blood is a vehicle of transport for immune cells and is not where immune responses occur. Surgical biopsies are invasive and non-random, so, for example, a fine-needle aspirate of a tumour could miss a significant feature of that condition.”

Knowing that the tissue around tumours often contains immune cells such as neutrophils and macrophages, Ploegh and his colleagues hypothesised that appropriately labelled VHHs — single-domain antibodies made by the immune systems of animals in the camelid family — might allow them to pinpoint tumour locations by finding the tumour-associated immune cells. (Ploegh’s lab immunises alpacas, his camelid of choice, to generate VHHs specific to immune cells of interest.)

Ploegh notes that VHHs’ extremely small size — about one-tenth that of conventional antibodies — are likely responsible for their superior tissue penetration and thus makes them particularly well suited for such use. For this study, the lab generated VHHs that recognise mouse immune cells, then labelled these VHHs with radioisotopes, and injected them into tumour-bearing mice. Subsequent PET imaging detected the location of immune cells around the tumour quickly and accurately.

“We were able to image tumours as small as one millimetre in size and within just a few days of their starting to grow,” explains the study's first author Mohammad Rashidian, a postdoctoral researcher in Ploegh’s lab. “We’re very excited about this because it’s a powerful approach to pick up inflammation in and around the tumour.” The study is published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The researchers believe that With further refinement the method could be used to monitor response to — and perhaps modify — cancer immunotherapy, which, though quite promising, has thus far met with great success in some cases, but has failed in others.

“To succeed with immunotherapy, we need more information about the tumour microenvironment,” Rashidian says. “With this method, you could perhaps start immunotherapy, and then, a few weeks later, image with VHHs to figure out progress and success of treatment.”

Adds Ploegh: “PET imaging should allow a much more comprehensive look at the entire tumour in its environment. Then we can ask, ‘Did the tumour grow? Did immune cells invade? What has happened to the tumour?’ And to be able to see this without going in invasively is a significant achievement.”

Source: Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research

Image Credit: PNAS

Latest Articles

PET, Tumours, immunotherapy, immune system, tomography, antibodies

A new technique that allows real-time, noninvasive imaging of the immune system’s response to the presence of tumours offers a potential breakthrough bot...